Why Gaming Will Never See Another Metal Gear Solid 1

The year was 1998. The shift from 2D to 3D games was already on the ground swinging with Super Mario 64, and Final Fantasy VII leading the charge. Then the so-called trilogy of stealth titles were released on the PS1. The first of these titles was the revolutionary Tenchu: Stealth Assassins, an experience that gave gamers a first taste of what stealth in a 3D environment could look like. Metal Gear Solid followed, creating a watershed moment for the entire genre that still reverberates today. But MGS1’s legacy isn’t a traditional one; in fact, its identity is next to impossible to emulate, especially today.

[embedded content]

One of the big defining factors of Metal Gear Solid’s unique identity is the hardware it was relegated to. There’s a certain atmosphere from early 3D games that gets lost in the sauce with modern rendering techniques. One can almost feel the cold, desolate winds of the island. The entire experience retains that cold bluish filter throughout with the exception of the green-tinted codec calls. While the falling snow around Snake isn’t exactly groundbreaking today, the unpredictable trajectory of the flakes combined with the light mist and fog really set a mood of isolation and tension. This pensive and cold visual style is punctuated by the moody musical score, even if occasional comedic alert stings contrast that in a quintessentially Kojima way.

Another aspect of MGS1 that isn’t likely to be replicated today is its fusion of retro and innovation with regard to gameplay. Like the original Metal Gear titles from the ’80s, MGS1 is largely played from a top-down perspective. It’s a perspective exceptionally common in older arcade titles for its simplistic 2D routing and rendering, but it was quickly becoming outdated by the time MGS1 released. Metal Gear Solid dynamically fuses both the top-down view and breakthrough cinematic framing in a uniquely unprecedented way.incredibly unique. The overhead camera resulted in more precise and capable stealth routing than an over-the-shoulder perspective could. This allocation of traditional perspective to gameplay and the newly developed 3D shoulder perspective to cinematics set a standard in story/gameplay framing. After MGS1, games started adopting more dynamic cameras that shifted based on story rather than sticking to just one perspective throughout.

This simple top-down camera angle allowed MGS1’s iconic stealth mechanics to flourish and thrive. First, there’s the iconic audio/visual indicators. The alert sting and accompanying exclamation mark have permeated pop culture just like Snake’s oh-so-clever box disguise became meme-worthy. These are all examples of super punchy and memorable feedback processes indicating an aspect of stealth gameplay. Just as the top-down camera allows ultra-precise radar-driven level design, so too do the various indicators and UX flourishes provide distinct and clear feedback of what’s happening to the player. Many modern games trip over themselves trying to come up with ultra-realistic stealth vision cones and sound mechanics. The sheer level of environmental detail in today’s games tends to obfuscate what matters most in stealth games: knowing what gets you caught. Metal Gear Solid’s simple and clean top-down layout and alert indicators are as much a breath of fresh air now as they were then. Players know immediately when they’re in the line of sight of an opponent, and it’s just as clear where to go to hide. No clunky textures getting in the way or even PS1-era fog effects to contend with. MGS1 is ultra clean and distinct. While indie games today love emulating retro visuals and mechanics, it’s unlikely we’ll ever get another AAA stealth game as punchy and precise as MGS1.

Nothing demonstrates the brilliant marriage of atmosphere and punchy mechanics better than MGS1’s boss fights. The Sniper Wolf encounter is a prime example. The industrial battlefield exposes Snake directly to the sniper’s line of sight. As a player, you’re tasked with navigating through the trenches, hiding from her rifle shots from above. It’s a tense feeling of being totally outmatched and utterly vulnerable—a theme that persists through other fights as well. A codec call from Otacon hints at the location of a sniper rifle that can greatly assist with the two Sniper Wolf showdowns, but most first-time attempts aren’t so privileged.

The tremendous scale of the hangar where players fight Vulcan Raven also emphasizes this feeling of vulnerability. Snake is like a tiny speck compared to Raven’s hulking mass and giant Gatling autocannon. It’s really only with the help of the convenient radar and minimap that Snake gets the better of him in the end. The shipping container pillars provide a fun and engaging environment to sneak up on Raven and maneuver around his shots.

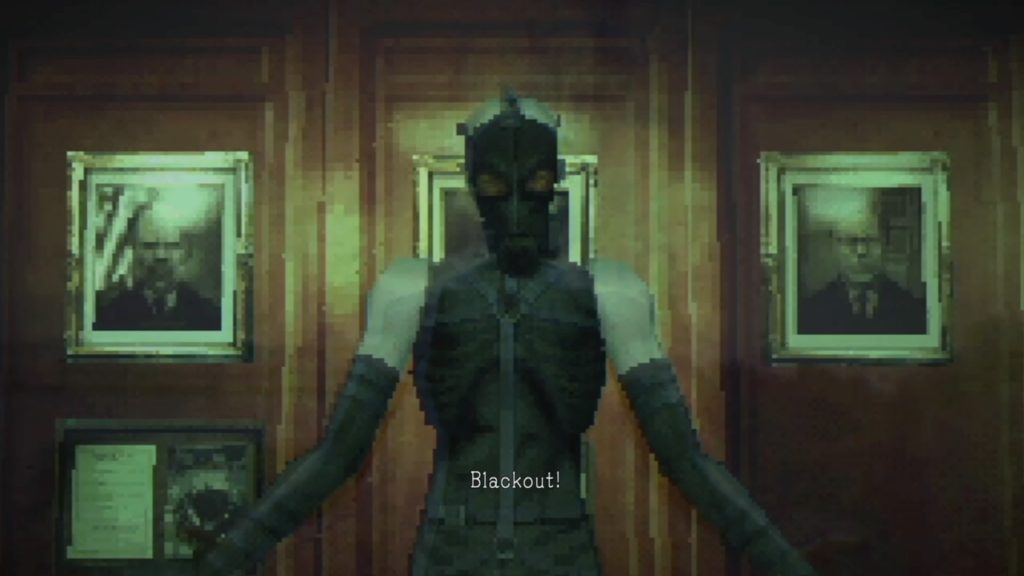

And of course, how can a Metal Gear Solid retrospective be complete without the mention of Psycho Mantis? This boss fight became the de facto example of fourth-wall-breaking design in games for decades. It’s a psychological fight more than a reflex-dependent one. And it’s a fight that forced the player to think outside the normal rules of video game logic. What other boss in history was overcome by changing controller ports on the system console? Psycho Mantis even forms a kind of personal connection to the gamer with the memory card reading. This psychic trickery perfectly demonstrates the kind of gameplay/story integration Kojima has been so well regarded for.

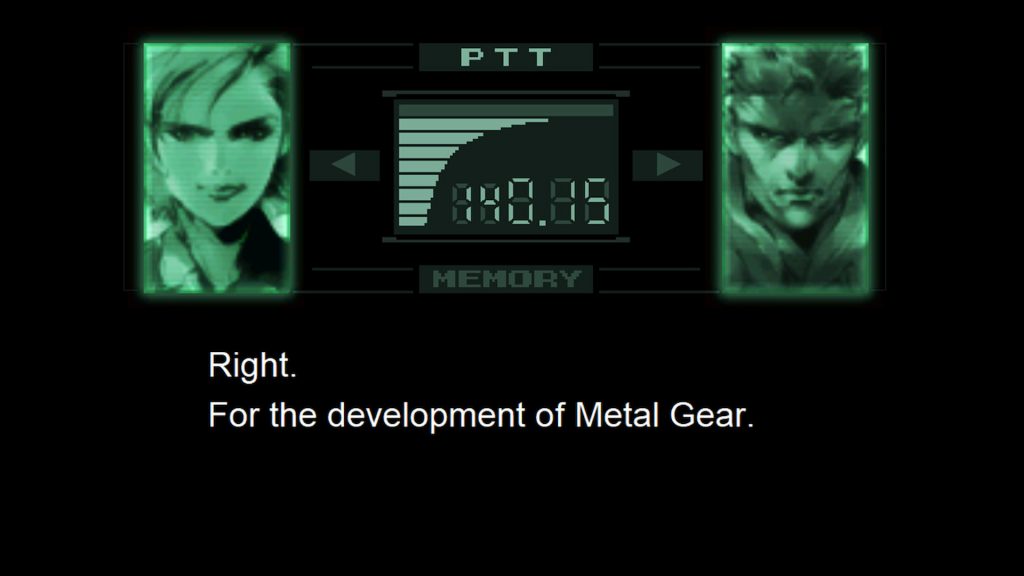

Not that the quality of the story relied solely on gimmicks and tricks to impress. One glance at the voice talent confirms that. Without hyperbole, Metal Gear Solid gave us the best voice acting of the PS1 era, and it’s not even close. I love the cheesy voices in games like Mega Man 8, of course, but MGS1 supplied cinema-quality presentation that was simply unheard of in that era. And today, without David Hayter as Solid Snake, there’s nothing else that can replicate the voice cast from early Metal Gear Solid games, especially the first one. Much of the dialogue occurs within the context of the codec calls. Important exposition and mission details are handled through in-universe codec calls rather than some menu tab or text summary. What’s more, the codec was diegetic to the game world; it helped establish character development and context without breaking the immersion of the setting with extra menu clicks.

The plot itself was something of a rarity at the time. It took mature themes like nuclear war and genetic fatalism and didn’t reduce them to an arcadey, simplistic thriller. The themes of Metal Gear Solid are explored in depth throughout the series and sometimes expounded upon in lengthy diatribes by the characters. Many essays have been written on the themes of MGS—suffice it to say Kojima’s iconic stealth series helped catapult storytelling in gaming to new heights.

But nothing can quite capture that very peculiar and iconic atmosphere that the original PS1 Metal Gear Solid did. Even The Twin Snakes remake eliminated some of the old-school charm with its cleaned-up visuals and ramped-up action. The classic minimalistic tension of the PS1 original was lost in translation, if just a bit. I mean, Snake backflipping off missiles was admittedly rad, but admit it—some of that cold, isolationist grit was lost. As such, the original Metal Gear Solid remains a unique gem of the PS1 era, one that cannot easily be replicated or captured.

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, GamingBolt as an organization.

Comments are closed.